Look out for the N-rays!

How does confirmation bias affect physics?

The Discovery of N-rays

France, 1904

Professor René Blondlot is about to make physics history.

Just last year, he announced his discovery of a previously unknown part of the electromagnetic spectrum: N-rays. Allegedly, these rays are emitted by almost all objects and have a host of bizarre properties, like the ability to change the brightness of sparks and improve the resolution of distant objects.

News of his discovery spread rapidly throughout the physics community, but many were unable to reproduce his experiments. Amidst the resulting scepticism, Nature sent Professor Robert W. Wood to Blondlot’s lab to investigate things further.

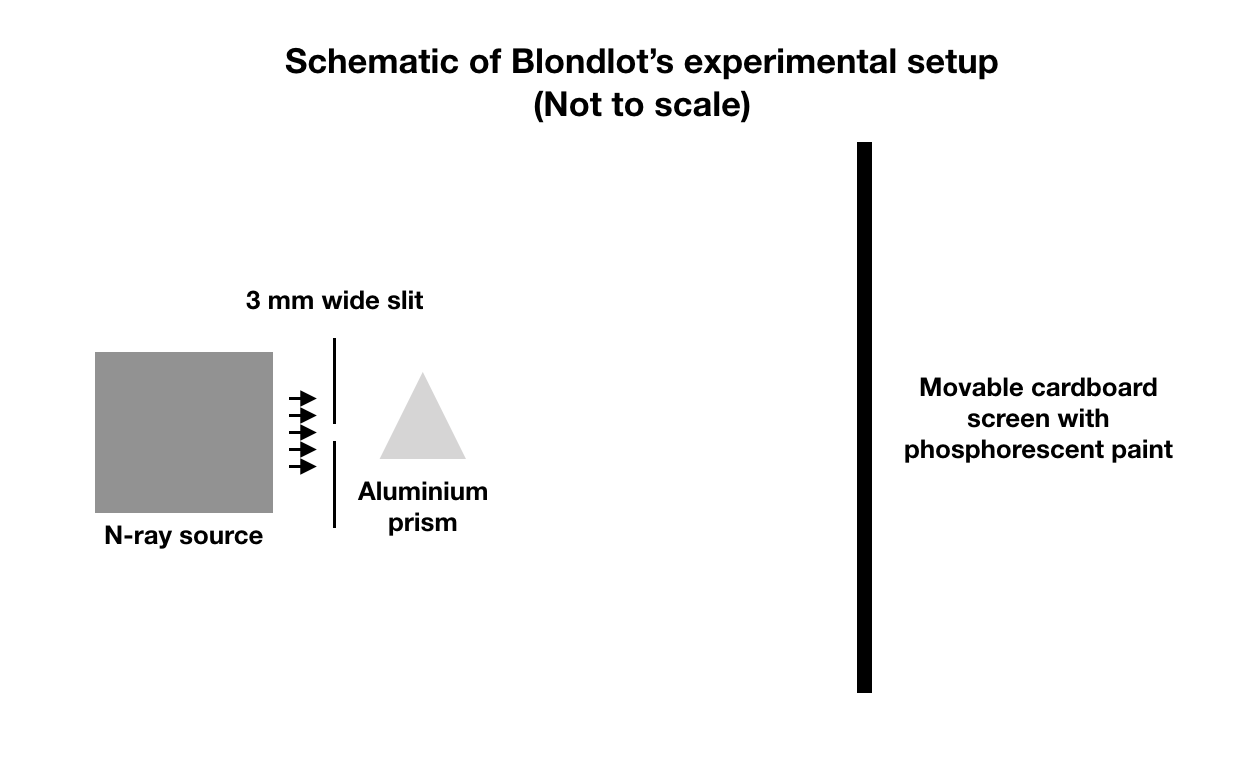

This is where we are now – a dimly lit physics laboratory at the University of Nancy. Robert Wood watches with scrutiny as Blondlot and his lab assistant run through their demonstration. The alleged N-rays are split using an aluminium prism and observed using phosphorescent paint on a screen, which should glow ever so slightly when the rays impinge upon it. In order to see the effects, the room has to be very dark, and the eyes of the observer sensitive to even the most minute changes. If Blondlot is right and N-rays do indeed exist, a distinct spectrum will be observed. With everything meticulously set up, all that is left to do is to let physics do its thing.

Wood watches with anticipation and sees something truly remarkable: absolutely nothing. Blondlot on the other hand, is absolutely convinced that the spectrum is distinctly visible, and he attributes Wood’s inability to see the pattern to a “lack of sensitiveness in the eye”. In light of these assertions, Wood proposes a follow-up test: he would adjust the aluminium prism, and Blondlot would have to tell when the changes were being made and how the prism was aligned.

Secretly though, Wood removes the prism altogether, ruining any chance of the spectrum being observed. But neither Blondlot nor his assistant detect any change – they remain convinced that they see the same pattern, utterly oblivious to what has happened.

Wood’s conclusions are quite self-explanatory:

“I am not only unable to report a single observation which appeared to indicate the existence of the rays, but left with a very firm conviction that the few experimenters who have obtained positive results have been in some way deluded.”

Robert W. Wood, in his paper The n-Rays

Confirmation Bias

Coming back to the present, we now know that the purported N-rays were just a figment of the imagination. This is true not just of Blondlot and his assistant, but also of the other physicists who claimed to have replicated his experimental findings. How could all of these scientists have believed so firmly in the existence of non-existent rays? The answer is confirmation bias, and is also the delusion that Wood alluded to. This involves favouring information that conforms to our beliefs while ignoring evidence to the contrary.

The reason for this bias is not entirely clear, but it likely stems from our natural impulses, such our tendency to prefer coherent narratives in thinking. This has been shown in MRI studies, where observed brain activity suggests active yet unintentional attempts to minimise cognitive dissonance. This leads to both avoidance of contradicting information because we do not like to be wrong, and seeking supporting evidence because we like to be correct.

In physics, there are two main ways in which this happens. The first of these is the biased search for information. In Blondlot’s experiment, he was explicitly looking for a miniscule change in the luminosity of phosphorescent paint. It appears that he tried so hard that he managed to force it into (his) existence!

The second way is through the biased interpretation of information. This could be through assigning more weight to certain results, or by simply ignoring evidence that supports alternative explanations. As previously mentioned, one of the apparent features of the N-rays was that it could change the brightness of sparks. It turns out that these changes were in fact due to normal, random fluctuations that sparks usually undergo regardless of any intervention. However, when Blondlot observed such fluctuations, he quickly attributed them to the effect of the N-rays. This just goes to show that our expectations can really distort how we view things.

What should I do?

The damage can be great if confirmation bias is ignored. Incidentally, Blondlot’s reputation was brought to its knees, and he never recovered from the resulting public humiliation. Allowing biases to remain unchecked during the research process can also diminish both the quality of collected data and the accompanying analysis.. Imagine having to repeat an experiment from scratch all because of this… ugh! It can even sustain false theories despite contradicting evidence.

Eradicating the bias, however, is not always a simple process. Consider the following question:

Q: Your physics experiment stubbornly refuses to obey the laws of physics. What should you say? (You may choose one or more answers.)

(A) “It’s probably just random error”

(B) “I’ll fake the data… Who could possibly know?”

(C) “What have I done wrong this time?”

(D) “Physics is broken!”

Options A to C all describe situations of confirmation bias – in some sense, a denial of the existing evidence. Option D would therefore be the “correct” option, right? As you can probably tell, things are not so simple. For instance, if the physical law that is violated is very well established experimentally, there is probably more reason to believe that something has gone wrong than to declare “the end of physics as we know it”. Of course, there is also some chance that the law is indeed wrong, but this would be very unlikely and the chances would have to be weighed accordingly. You could therefore imagine how difficult it might be to suggest that a widely accepted law is flawed in some way.

Although it is practically impossible to eliminate confirmation bias completely, there are fortunately still some things that we can do to mitigate it.

- List ideas as to why the hypothesis might be incorrect. It can also be helpful to list alternative hypotheses and to see whether these are consistent with findings. Knowing about these other possibilities can help limit how much we search for evidence that only supports a particular view.

- Constantly ask yourself whether you are processing information in biased fashion. What is your first reaction to a book titled “The Moon Landing Hoax”? Why do you have that particular impression? Would it be a good idea to look at what the book says? Doing this does not mean that you have to agree with whatever you see; rather, it means being aware of our reasoning and identifying weaknesses in how we see information. Beyond the individual level, there are also other ways of combatting confirmation bias. One of these is scientific peer review, although it is important to note that this process is itself prone to the bias! It is also useful to have attempts to replicate the original experiment. As a matter of fact, this was what eventually spelled doom for Blondlot’s N-ray theory – the failure to replicate the experiment consistently and independently. These methods are far from being a cure-all, however.

With the benefit of hindsight, it can be very easy to dismiss the N-ray debacle as a singular case of delusion, and to think that this is not relevant to ourselves. But it is important to realise that no one is infallible. Everybody is susceptible to confirmation bias, and if we’re not careful, there’s no telling whether or not we might see N-rays of our own.