Challenges around definitions of algorithmic progress

Brief and unpolished thoughts about issues pertaining to definitions of algorithmic progress.

If you care about understanding the future of AI progress, then you should care about algorithmic progress. Every year, researchers tinker with new neural network architectures, optimizers, and other algorithmic changes to push the state of the art forward. Sometimes this looks like the typical humdrum of gradual improvements, and other times you get something like the Transformer, which rapidly transformed the landscape of natural language processing after its introduction.

But while there’s broad consensus about the importance of algorithmic progress for improving AI systems, it’s tricky to quantify just how important it is. How fast have algorithms been improving? How important are algorithmic improvements relative to scaling up training compute? What kinds of algorithmic innovations are the most important?

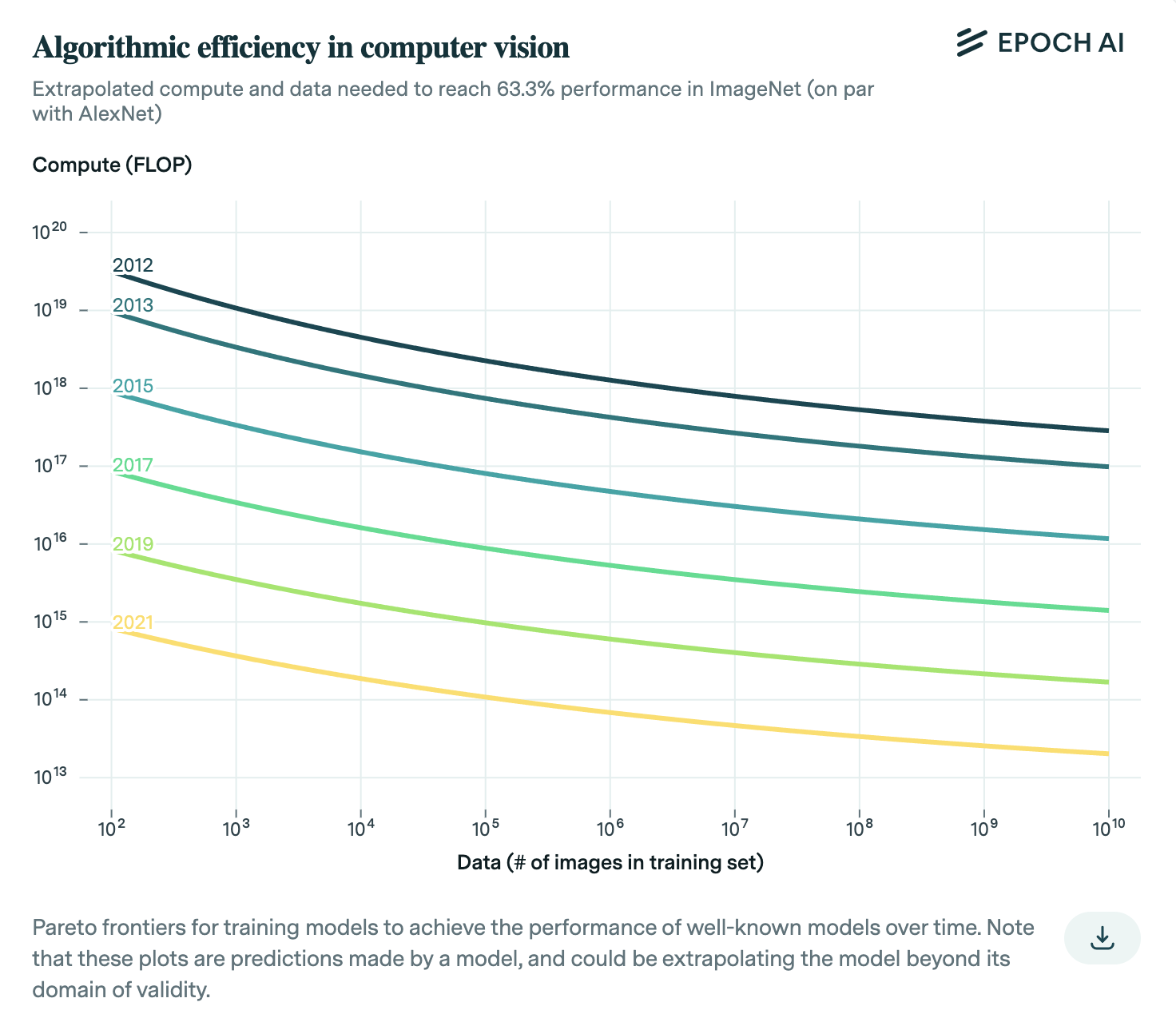

One standard way to answer these kinds of questions is to define algorithmic progress in terms of reductions of resources required to attain a certain level of performance. For example, Hernandez and Brown (2020) measure the reduction in the training compute required to reach AlexNet level performance on ImageNet. In this way, “better” algorithms are the ones that use a budget of computational resources more efficiently.1 The rate of algorithmic progress can then be estimated by looking at how quickly the required compute falls over time - this is shown in the graph below (from Erdil and Besiroglu (2022)).

This seems somewhat intuitive, but there are some puzzles here. For example, what does “level of performance” mean? At least on the surface, it seems like this definition could depend on which benchmark we’re referring to, such as Penn Treebank or WikiText-103. The metric could also matter: while log test perplexity has been decreasing fairly steadily across time, context lengths have followed a different growth dynamic - increasing slowly until around 2022, when FlashAttention was introduced, after which context lengths increased dramatically. Depending on which metric you track, you could come to pretty different conclusions about the rate of algorithmic progress.

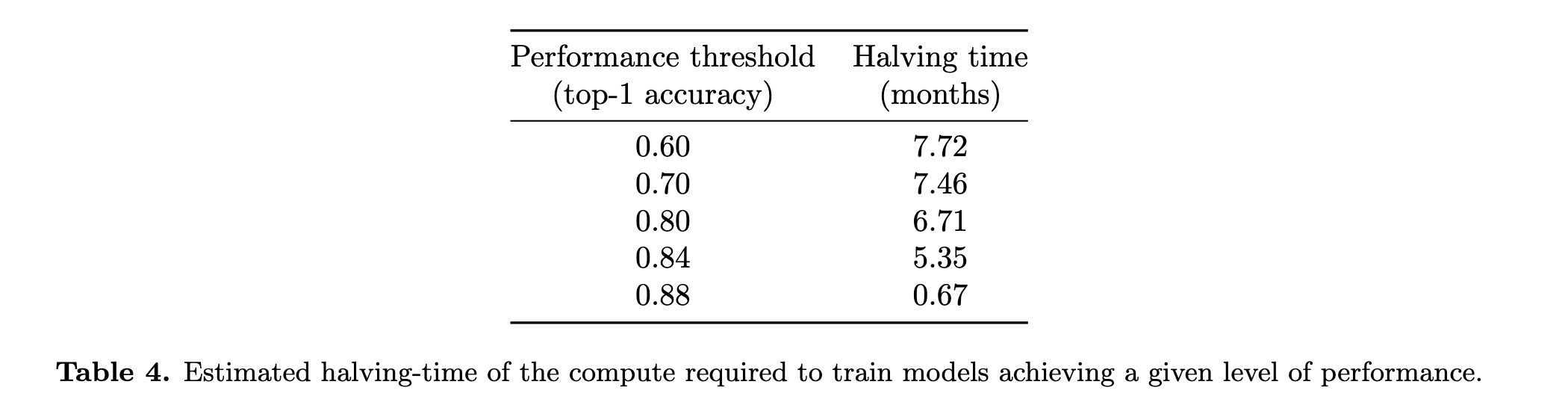

Even if we agree on which dataset to use, we still need to choose a particular performance level. Hernandez and Brown looked at AlexNet-level performance, but what if they had chosen a difference threshold? Erdil and Besiroglu (2022) illustrate what happens in one of their appendices:

As we can see, the estimated required compute halving time can differ by an OOM depending on the performance threshold! To try and address this issue, Erdil and Besiroglu fit a statistical model based on neural scaling laws, such that the doubling time can be inferred from the model parameters and without specifying any particular performance threshold. In effect, this averages over different performance thresholds to arrive at a single growth rate. Unfortunately, using this estimation approach poses its own problems. It requires a lot of data, but since high-quality data is seldom abundant, we can end up with noisy estimates of the rate of algorithmic improvements.2 It also assumes a particular form of neural scaling law, which is unlikely to be exactly true in practice.

While I could go on rambling for ages, I’ll briefly mention one more thorny issue that one needs to grapple with when thinking about definitions of algorithmic progress. Suppose you want to measure algorithmic improvements between 2020 and 2024. Which of these is larger: the compute increase needed for 2020 algorithms to match the performance of 2024 algorithms, or the compute decrease needed for 2024 algorithms to match 2020 algorithms? These two ways of defining algorithmic progress are often conflated with one another in discussions even if they might have different values (especially if the years are further apart, e.g. 2014 and 2024). To me this seems like an important distinction, but we don’t much reliable experimental evidence to anchor our intuitions, so I’ll leave further discussion on this point for future work.

So, what’s the takeaway from all of this? I think the key message is this: there are many surprisingly tricky details around definitions of algorithmic progress… and these are just issues relating to definitions! There’s still a lot that we don’t know about how algorithmic progress works more generally (more on this in future posts). Given the importance of algorithmic improvements in determining future AI progress, I think it’d be valuable to get a better handle on this.

Thanks to Jaime, Tamay, Tom, Lukas, Eli and Ege for discussions that led to this post.

-

Note that we don’t measure algorithmic progress using the typical kind of asymptotic analysis that’s done with algorithms like Bubble sort or Merge sort. The reason for this was pointed out by Hernandez and Brown (2020), that it’s not very tractable for the complicated neural network architectures that are commonly used. ↩

-

Indeed, the confidence intervals from both Ho et al 2024 and Erdil and Besiroglu 2022 are pretty wide. ↩